Black Medical Excellence Then, Now, and Forever

Regardless of what month it is, Black history is always worth celebrating. History is a living thing that mostly has been written and rewritten by those with privilege and power. Oppressed people have not been able to participate in the creation of history to the same degree, but today we’re living at an amazing time when we have access to an immense amount of knowledge about ourselves and our cultures at our fingertips. We are able to rediscover these people, civilizations, and achievements from our past and give them their due. However, the point of re-examining and celebrating our history is not to focus solely on the past, but also to use it to see our present more clearly. And if the way we see our present changes, we can change the way we see our futures.

Especially in the field of medicine, we deserve to know, celebrate, and have a place in writing our own history of Black excellence, which is why we’ve put together a quick overview of the ways in which people of the African diaspora have always been, continue to be, and will forever be innovators in the field of medicine and healthcare.

Egyptian Medical Excellence from the Way, Way Back

Black excellence did not start when we arrived on the shores of foreign lands under conditions we had to overcome. It’s ancient and shaped many of the modern advances we have today in several fields including arts, science, and medicine.

Let’s be clear: traditional medicine, which gave rise to modern medicine, was formed and developed from the knowledge, theories, and skills of indigenous cultures. When we look at the medical contributions of these ancient cultures, the Egyptian civilization is one of the greatest and oldest of all time (not to diminish any of the incredible contributions of Asian, American, or other advanced civilizations elsewhere). It was in ancient Egypt from about 3300 BCE to 525 BCE where the first evidence of modern medical care can be found. Literally, the world’s first documented physician, Sekhet'enanch, was Egyptian.

© David Erroll - Doctor Offering Medicine

Egypt had a rich culture for medicine (and A LOT of other things), developing an intricate medical hierarchy and system that looks a bit like our current medical care structure:

Ordinary doctor aka 'swnw'

Overseer of doctors aka 'imyr swnw'

Chief of doctors aka ‘wr swnw’

Eldest of doctors aka 'smsw swnw'

Inspector of doctors aka 'shd swnw'

There is also evidence that describes ‘imy-rt-suwny’, a female director of women physicians, suggesting Egyptians had women who practiced medicine.

Herodotus, a Greek physician who is considered to be the ‘father of history’ said of the Egyptians in about 425 BCE, ‘The practice of medicine they split into separate parts, each doctor being responsible for the treatment of only one disease. There are, in consequence, innumerable doctors, some specializing in diseases of the eye, others of the head, others of the stomach, and so on; while others, again, deal with the sort of troubles which cannot be exactly localized.’

Though different from how we would currently define medical ‘specialization’, Egyptian doctors earned reputations for their skills treating specific diseases and made incredible medical discoveries in the fields of surgery, neuroscience, cardiology, and gynecology. Here are just a few claims to medical fame that ancient Egypt holds:

The Ebers Papyrus, the oldest preserved medical document. Credit: SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

The first written description of the brain and the cerebral cortex.

They were the first to document the circulation of blood in the body.

Egyptians were the inventors of clinical observation and were the first to describe conditions like migraines, epilepsy, strokes, and Bell's palsy.

The oldest preserved medical documents, the Ebers papyrus, come from Egypt documenting scientifically sound procedures for surgery, family planning, and emergency medicine.

We should mention that Egyptian medicine looked a lot different than our medicine today. It was highly influenced by magic and spiritual beliefs as was common in most ancient cultures. All of this is to say that Egyptians are responsible for an incredibly nuanced degree of medical observation and discovery that worked in the context of their beliefs. Their system blended science and religion in a way that influenced and paved the way for Greek medical advances and all of the advances that followed that. To say that Egypt is the ‘mother of medicine’ is not overstating anything.

The Pioneers of African American Medicine:

Looking forward to more modern times in the United States, we can find hundreds, if not thousands, of ancestors who have advanced medicine and paved the way for more minorities to join and excel in the medical field. We couldn’t possibly cover them all here, but we wanted to highlight a few that have inspired us. We have the army of folks who broke through segregated barriers in the 20th century and began the hard work towards health equity like members of the Black Panther Party who set up a national screening program for Sickle cell, Daniel Hales Williams, MD, who performed the world’s first successful open heart surgery, and many more. All of those folks were sitting on the shoulders of people who even before their time were working to save lives and heal people.

Onesimus: The Slave who Lead to the Eradication of Smallpox

Onesimus was a West African enslaved person living in Massachusetts in the early 1700’s, at a time when smallpox was one of the most deadly and highly contagious diseases. It killed thousands of people in the American colonies, decimated indigenous communities who had no immunity, and was highly feared. Killing it’s victims 30% of the time, whenever smallpox cases arrived in a city, there was panic and people would flee for their lives with no idea what was the cause or how to prevent the spread.

Onesimus shared with the person who owned him that he had previously had smallpox and underwent an operation that cured him and ensured that he would be free of the illness forever, a process known to many enslaved people and also used in Turkey and China at that time. This procedure involved rubbing pus from an infected person into an open wound on the arm under the supervision of a physician. By introducing the infection to the body, the person became inoculated to the disease in most cases by activating their immunity so the body could respond in the future when exposed.

It was during a smallpox outbreak in 1721 in Boston that the theory of inoculation was able to be tested by a physician who Onesimus’ owner had told about it. About half of the city's residents became ill. The physician, Zabdiel Boylston, started inoculating his family and his enslaved workers using the method Onesimus had described. Of the 242 people he inoculated, only six died— less than 3%t compared to the more than 14% rate of death among the people in Boston who didn’t receive the procedure. The process of inoculation is different from the safer form of vaccination, but it laid the groundwork for the smallpox vaccine developed in 1796. Today smallpox has been declared entirely eradicated thanks to worldwide immunization and we have Onesimus, a West African enslaved person to thank for it.

Dr. James Durham: From Slave to Physician

James Durham was born an enslaved person in Philadelphia, PA in 1762. Throughout Durham’s early life he was owned by different physicians who allowed for him to become highly educated and learn about the field of medicine. In 1783, when Durham was 21, he was sold to a physician in New Orleans who valued Durham's skills and knowledge and helped him get hands-on experience by working with patient’s of various races. This is the first recorded instance of an African American trained in medicine treating people of any racial background.

Durham earned money treating patients under the tutelage of his owner and soon bought his own freedom and began to practice medicine independently, continuing to see patients of various racial backgrounds. He was well known for his treatments of diphtheria, an infection of the nose and throat, and saved many lives during a yellow fever epidemic in 1789. His reputation caught the attention of Dr. Benjamin Rush, one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence and one of the most widely respected doctors of the time. Rush was so impressed with Durham's success in treating patients with diphtheria, that he read Durham's paper on the subject before the College of Physicians of Philadelphia.

Eventually Durham was barred from practicing medicine by regulations that restricted the ability to practice to only those who had formal medical degrees (which it was not possible for him to receive at that time), but his reputation and work began to open doors and minds that eventually other great Black physicians would walk through. Today, he is widely acknowledged as the first recognized African American to be a physician in the United States.

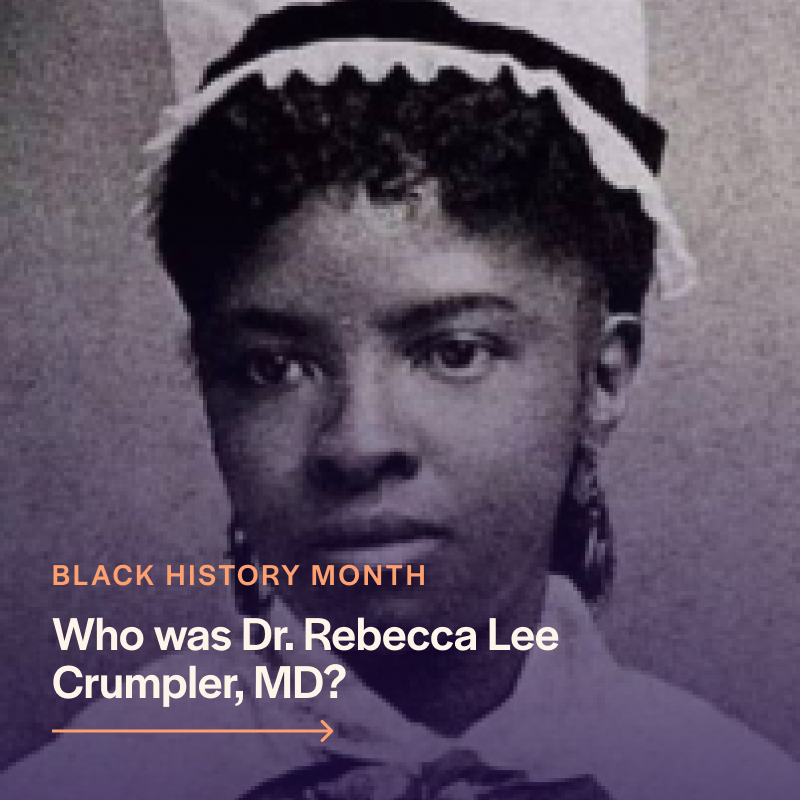

Dr. Rebecca Lee Crumpler: The First Female, African-American Physician

Born in 1831, Rebecca Lee Crumpler, was raised and influenced by an aunt who cared for sick neighbors and practiced traditional healing practices. After several years of practicing nursing she enrolled in the New England Female Medical College, graduating in 1864 as the first African-American woman to earn an M.D. degree.

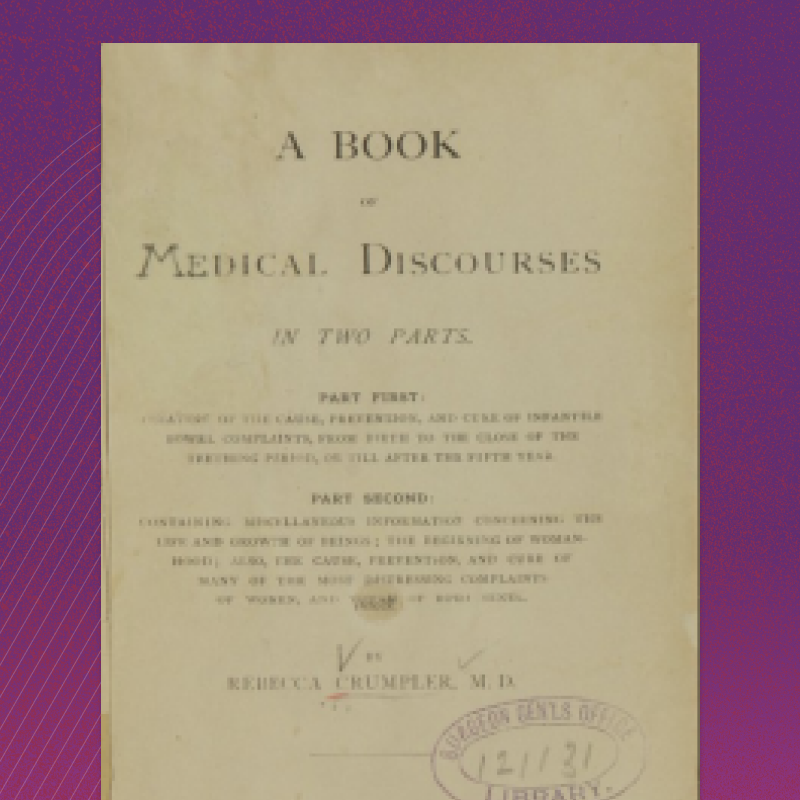

Once the Civil War ended in 1865, Dr. Crumpler moved to Richmond, Virginia to join other African-American physicians treating the people of recently freed communities, providing the only medical care those people could receive through the Freedmen's Bureau and various missionary groups. Dr. Crumpler used this opportunity to to study and document the diseases of women and children, eventually publishing the first medical text ever by an African-American, Book of Medical Discourses, in 1883. What she accomplished in her lifetime is impressive for any time and any person, but beyond exceptional for a Black woman during the Civil and Post- Civil War eras.

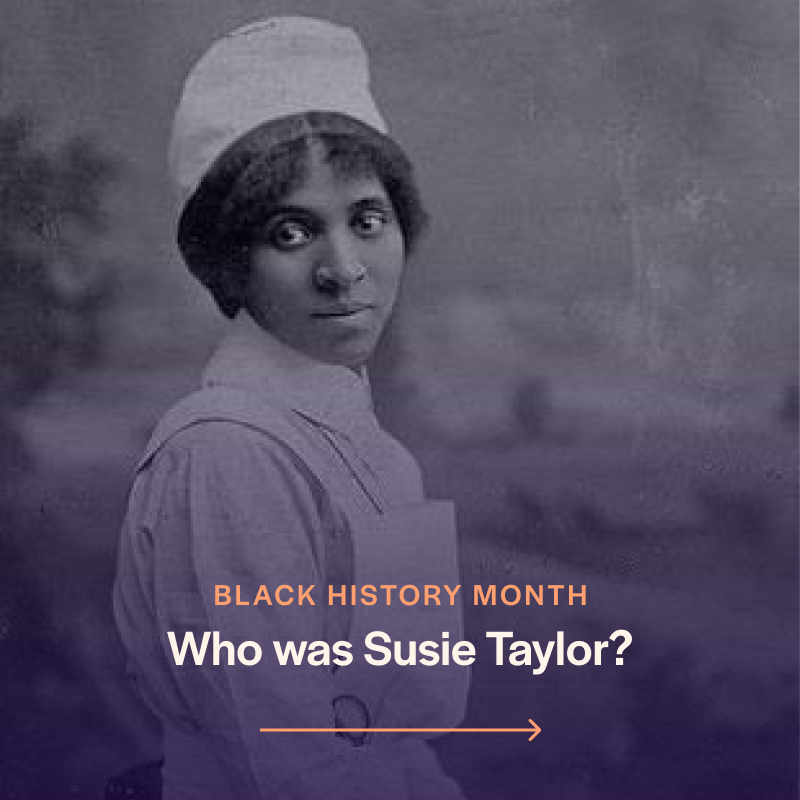

Susie Taylor: Educator and Civil War Army Nurse

Born into slavery in Georgia in 1848, Taylor (then Susie Baker) was educated and became literate by attending secret schools run by free Black women, something that was not only illegal at the time but highly dangerous. Susie escaped when she was 14 while Union forces attacked the Confederate Fort Pulaski, and became a school teacher the same year. As the war continued, Susie joined the first Black regiment in the US Army, the 1st South Carolina Volunteers. This unit consisted mainly of Gullah Men from Georgia and South Carolina who had escaped or had been freed. Because of her ability to read and write she was given a position teaching members of the regiment how to read and write while also serving as a nurse and caretaker, treating hundreds of wounds and diseases including cholera, diarrhea, malaria, measles, pneumonia, and typhoid. It’s of note that Harriet Tubman also served as a nurse, scout, and spy for this regiment, though it’s unclear if the two female pioneers knew each other.

Despite performing all of the duties of a nurse and much more Susie was always technically classified as a “laundress” in her unit which meant she was never paid fairly and didn't receive a pension as was her due. Today she is recognized as the first African American Army Nurse.

“There are many people who do not know what some of the colored women did during the war.”

Much of what we know about the happenings of the 1st South Carolina Volunteers activity and contributions comes from Susie’s own memoir, Reminiscences of My Life in Camp, a rare perspective on the Civil War told exclusively through the voice of an African-American woman. Published in 1902, Susie’s work insisted that Black soldiers and nurses be given a place in the history of the victory of the Union in the Civil War

Black Medical History being made today:

There has never been a time in the United States that Black people have not been innovating and contributing to medical innovation. This legacy and tradition continues today, where equality and access are certainly better than it was in the 18th and 19th century, but by no means is it a level playing field. Today only 5% of active physicians identify as Black or African American, while making up 14% of the US population. There are many factors that contribute to this and make it a harder road for Black medical professionals to gain entry to the field, but once they do, people of the African diaspora are making incredible contributions to the advancement of medicine.

NIH's Dr. Kizzmekia Corbett discuss creation of a vaccine for the coronavirus with group of pharmacy executives. Via ABC News

For example, American viral immunologist, Dr. Kizzmekia Corbett, is one of the National Institute of Health's leading scientists behind the government's search for a COVID-19 vaccine. Corbett is part of a team at NIH that worked with Moderna, the pharmaceutical company that developed one of the two mRNA vaccines that has shown to be more than 90% effective. Dr. Corbett is passionate about doing this work and gaining trust of the Black community in vaccine therapies, a trust that has been actively violated throughout American history.

Cutting edge medical innovations are not only coming from those of us in the West, but also straight from African inventors and innovators like Brian Turyabagye and Olivia Koburongo from Uganda who have invented a biomedical smart jacket that can increase the speed and accuracy of the detection of pneumonia, a deadly condition in many parts of the world especially for newborns. Mama-Ope, or "Hope for the Mother", is the name of the device which measures body temperature and other medical data, analyzes it, and sends a diagnosis through Bluetooth to the medical provider. The device is currently in the prototype stage, but exemplifies the innovation coming from Africa directly.

Mama-Ope isn’t the only innovation, or even one of a few that could shape a new medical future for us. Nigerian born and educated, Oshi Agabi, has created a device that combines stem cells and silicon chips that has applications in security, agriculture, and healthcare. Agabi’s Silicon valley based company, Koniku Kore, merges cutting edge technology with neurobiology to detect things like bombs to sniff out particles common in those devices the way in which trained canines do. Similar research and development is exploring the ability to use this technology to detect cancer cells in the body.

Black Medical Excellence Forever

Afrofuturism is a cultural movement in art, fashion, music, etc that seeks to reimagine the history of the African diaspora using science fiction and fantasy to create a view of technically advanced and thriving futures of Black peoples. We’re here for it, love it, and need it. But doesn’t this documented history of the achievements of our ancestors we’ve examined sound like science fiction and fantasy? There were real life Black super civilizations like Egypt who dominated in their time and laid the foundation for other cultures who came after them. People who were born into slavery and saved hundreds of lives with their medical skills sound like superheroes. Innovations that are occurring today sound like science fiction that we could imagine coming from Shuri’s Wakandan lab.

The excellence and contributions of our ancestors from the African diaspora to the field of medicine have and continue to inspire us at Spora Health to imagine a healthcare system that is just as exceptional as the shoulders we stand on.

Are you ready to start your healthcare journey with a culturally competent primary care provider? Sign up for Spora Health today and book an appointment.